Is the aim of philosophy truth or understanding?

*bong hit* philosophy is, like, a socially-embedded field, man... we read it to understand people and society... *cough* *hack* *weez*

note: I don’t think the conclusion of this piece is, in the end, revolutionary, but I’m saying it anyway because I do think it’s important to say somewhat obvious things sometimes. also I’m something of an autodidact when it comes to philosophy, but I’m writing on metaphilosophy here, which I have read basically nothing on [directly, anyway. arguably like most philosophy is also some sort of metaphilosophy, but i digress]. just a disclaimer if you’re very scrupulous about wanting to know if you might read something that could be wrong

"What is the aim of philosophy?" As someone who has had an on-again, off-again interest in philosophy since high school, I was intrigued five years ago when I saw this question in the 2020 PhilPapers survey (a survey of academic philosophers investigating the popularity of different positions in the field, following a similar but smaller survey released in 2009).

I had never really thought of the question before. My knee-jerk reaction, though, was to say it was the truth. My interest in the subject, after all, was piqued by (and I do really mean this) in trying to find the “right” answers to things like the hard problem of consciousness and the age-old question of which ethical theory was correct.

In 2020, many philosophers did agree with this intuition.

The two numbers mean that of the philosophers who responded to the question, 42% included truth/knowledge as one of multiple answers to the question (they had the option of selecting more than one option, like voters on a sports hall of fame ballot); and about 18% included it as the only option.

But more philosophers selected a different answer.

These days, I’m inclined to say these results speak to something that’s basically right: understanding is a more critical aim in philosophy than knowledge is.

Earlier today, Barry Lam (who has a great book on discretion and its infelicitous marginalization in modern bureaucracies—something that’s intrigued me a lot, particularly as a lawyer interested in administrative law, statutory interpretation, and legal theory; I recommend it a lot) wrote a piece on here that gets to this idea.

You should read the piece yourself—it’s not that long—but the gist is that Lam argues that there’s a disjunction between what’s incentivized in writing as an academic philosopher, as compared with what people actually value most in pieces of philosophy, with some interesting implications. I’ll restate and summarize the points relevant for this piece (and because I really like talking about Derek Parfit).

Lam cites Derek Parfit (one of the very most important anglophone philosophers of the last hundred years 😌, who published only two books in his life) to illustrate this incongruity between what’s incentivized and what’s valued.

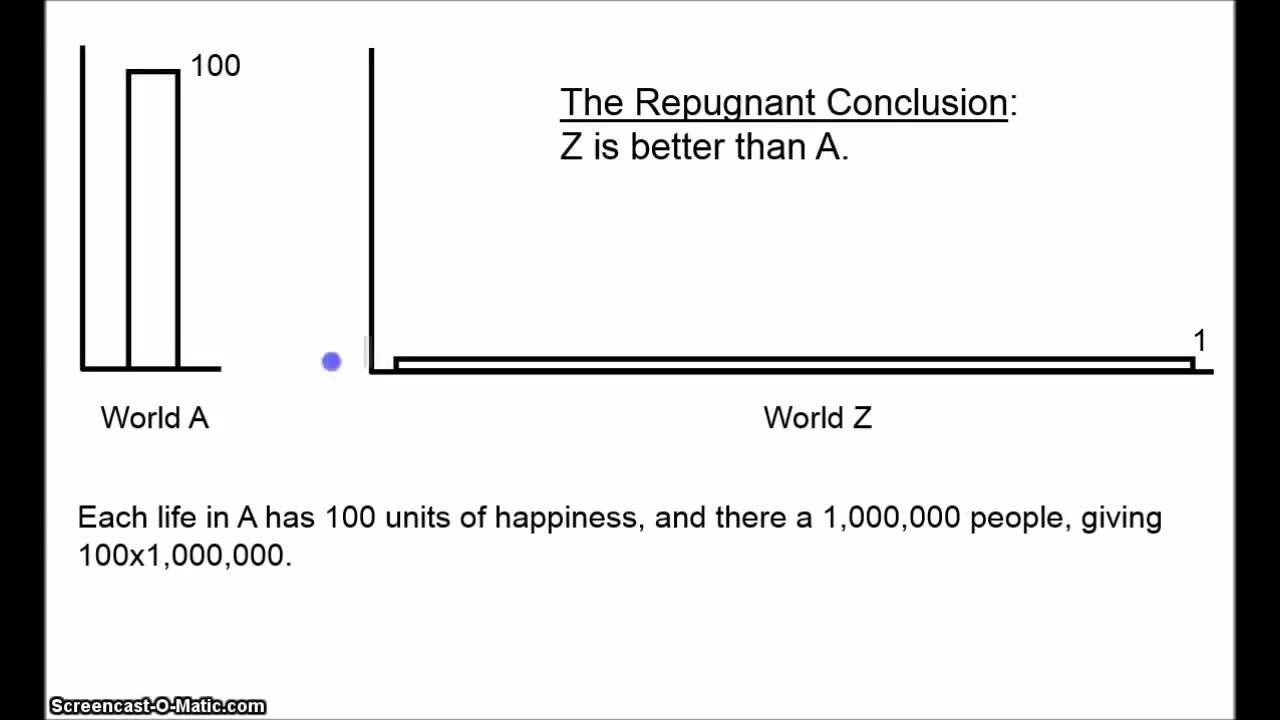

Reasons and Persons, his first book (published in the 1980s), was his less careful but far more significant work of his two books. Like many books in philosophy, it was the culmination of his mostly isolated thinking about different subjects for about a decade or so. But despite its typical enough pedigree, because of Parfit’s unique and trenchant perspective on things (also, arguably because he was writing in a fecund time period for moral philosophy after a number of decades of the subfield’s marginilization) and because of his memorable presentation of ideas, with novel thought experiments and his usage of (then, pretty rare) graphs to present his ideas, he ended up revolutionizing three different subfields in philosophy.

More than anything else, though, I think it’s popular because of its subject matter. There simply had never been sustained treatments of ideas like those now central to, e.g., population ethics (when/how/why is it moral to create children? is it possible to compare the welfare between different populations? how do we resolve any resultant paradoxes?) in a serious, 400-page book before. Reasons and Persons shook the field mostly because it raised new questions, not because it came close to conclusively answering them (which isn’t to say that Parfit’s argumentation throughout the book was not compelling).

His second work, On What Matters (published in the 2010s), meanwhile, aimed to answer old questions more than it asked new ones. It was far more careful (and long; it’s a very beefy three-volume work, and it ended more than it finished, as Parfit died before he could write another planned volume) than Reasons and Persons, with much of the second two volumes responding to criticisms of ideas other philosophers lent to ideas underpining his initial argumentation in Volume 1.

Like, most of On What Matters is Parfit responding to critics. Volumes 2 and 3, which do have (putative) substantive aims of their own, in large part proceed by Parfit spending bundles of chapters each to talk about, e.g., why he thinks people like Blackburn and Gibbard and Williams (moral anti-realists) are either completely off the mark or secretly agree with him. It’s a great work; it’s very tightly argued in my opinion, and it’s had a very significant influence on its own, but it’s not seminal the way Reasons and Persons is.

Lam says that it was less influential, in large part, because it’s pedantic. I think this is right. Even though Parfit is very thorough, in the end, because so much of his argumentation hinges on specific, hyper-local questions like “what is the ontological status of an agent-independent reason,” there’s just not much to talk about or latch onto unless you yourself are similarly invested in such questions.

Also, I might add, the questions Parfit addresses in On What Matters (by and large) weren’t new. They had been major subjects, in some form or another, in analytic philosophy at least since the 1950s and 1960s, and probably earlier than that, depending on how narrowly you define their contours.

Anyway, Lam points out: the fact that Reasons and Persons outstrips On What Matters in terms of significance is, on the one hand, strange (when one considers how journal articles and the like are reviewed—people care a whole lot about whether what you’re saying is missing something in any way shape or form, much more than any other desiderata, like if what you’ve written has an ounce of personality to it) and on the other, completely unsurprising—people like works with a lot of personality, that touch on new ideas.

Like, the conclusions of On What Matters are more likely to be correct than Reasons and Persons, based on the way it’s written. Parfit meticulously responds to tons and tons and tons of counter-arguments throughout. Isn’t philosophy supposed to, ultimately, be correct?

Lam writes:

It has to be that philosophy, at least some of it, has an irreducibly aesthetic aims connected with certain aesthetic emotions. These aims are at odds with creation by committee. Good philosophy inspires in the way good art does. Parfit inspired curiosity in Reasons and Persons with thought-experiments that people still teach and think about. They even make for important plot points in Dr. Who and many other science fiction stories. On What Matters on the other hand, sought to eliminate curiosity by seeking to settle every question the curious reader might raise. Good philosophy is supposed to offer insight into the inner life, the thought and mental procedures, of the individual producing it. When that inner life is significantly different, or significantly similar, to yours there is a pleasure in your confrontation and engagement with such a mind, such an “other,” as humanities people love to put it.

His piece goes on to continue to discuss the philosopher as a singular auteur as someone far more apt to write works that actually interest people, than authors-by-committee (who write most journal articles are, in effect). They lack personality and care more about not offending or not trampling upon any possible precept of writing on a given subject that any one specific reader actually cares about. They’re far less likely to be interesting, which is something people do care about in philosophy, much more than in other fields.

But Lam ends the piece leaving the question of why this is the case for philosophy and not other fields somewhat open. He does contrast philosophy against science (where it’s far more obviously desirable to have cautious, multi-authored works that get people a smidgen closer to the truth), stating that philosophy has aesthetic aims where science doesn’t, and argues that being interesting is very important (at least insofar as he’s concerned; he states he’s more afraid of being uninteresting in philosophy than he is of anything else), in an under-recognized way.

But why? Why do we care more about being interesting in philosophy than we do in science?

Spoiler alert: it’s because the main aim of philosophy is understanding!

To start with a disclaimer: it's obviously the case that truth is an important aim of philosophy. Any piece of philosophy that does not seem to get at something that could maybe be true is garbage philosophy. The issue, though, with setting this as the principal aim of philosophy, is that 1) plenty of things that aren't philosophy also aim for the truth in a much more direct fashion (basically the totality of the natural and social sciences, to reference Lam’s example); and more interestingly and significantly, 2) a number of the most praised philosophers in history expressed ideas that very few readers, contemporaneous to them or current, have every really been convinced about. Nietzsche comes to mind as perhaps the most significant example.

Nietzsche is one of the most significant philosophers of modernity because, if you read his works, you encounter and come to understand a somewhat coherent counter-perspective on things like Christianity, morality, and yes, modernity that is incredibly difficult to find elsewhere. Works like On The Genealogy of Morals are not significant because they're likely to be true; they're significant because the mere fact that they could be true, or at least that they are not obviously wrong, has far-reaching implications. Nietzsche helps us understand things in ways unmatched by most other philosophers—it’s just that the understanding we gain from reading him is just a result of trying to figure out why he’s wrong in the first place.

There’s a reason why like 20% of significant books on philosophy find it expedient to devote a lot of time framing their thesis against Nietzsche, and it’s not because Nietzsche is a super-easy strawman to knock down.

People sometimes say philosophy is inquiry without any method. When a subfield of philosophy gains a method that (most) everyone can agree on, it becomes a science, branches off, and becomes independent from philosophy.

I think this picture is fairly simplistic and incomplete (I hear from philosophers of science, sometimes, that there is a bit of controversy about the link between fixed method and science), but I think it’s close enough to the truth to be usefully built upon. Well, then, if philosophy necessarily lacks a method or much in the way of any agreed-upon commitments in the first place, how can we use it to reliably get to the truth?

You as an individual, you, you smart, clever, sexy reader of mine, might be able to determine what’s true and what’s not in philosophy. But you certainly can’t trust that anybody else is doing that!

Instead, understanding makes a lot more sense to characterize the end of a (relatively) norm-less but still, undoubtedly, social inquiry.

When you read a work of philosophy you’re inclined to agree with (let’s say it’s on the existence of God), you feel as though you understand better what God is, and why He likely/definitely does/doesn’t exist. Another name for this is the truth about God, of course, but you can’t really be sure about that, given that most philosophers of religion will probably have something of a bone to pick with the reasoning of whatever work you just read. And when you read works about the (non-)existence of God you’re inclined to disagree with, you also *sigh, this is getting tiring* better understand what motivates people to have a different opinion on God. You might come closer to knowing the best version of the reasoning people employ to reach a contrary conclusion, helpful in knowing things about God, but even if their reasoning is comparatively poor, you still understand the kinds of mistakes people make about God, and maybe why people make them.

Also—and this gets more at Lam’s description of how Reasons and Persons was successful in a way that On What Matters wasn’t—charting new territory in philosophy, as Reasons and Persons did, helps push along the process of short-term understanding and hopefully long-term agreement, regardless of whatever specific arguments are made (though tight arguments are still important to demonstrate that we have yet more to think about an dunderstanding). As with Nietzsche, novel works reveal that there are new understandings to come to about familiar subjects.

So, to summarize: if philosophy is inquiry that’s less-than-fixed, but seeks to become more fixed, such that it becomes closer to something like science (I know ascribing this telos to philosophy will make some people, particularly continental-types, really mad, but let’s push forward), then two things are valuable in any given piece of philosophy. Either it comes to describe its object of investigation really well, or it comes close to that sort of success, but misses the mark in such a way that it reveals something mistaken about the way at least some of us think about it.

In either case, having good, tight arguments is useful. And if what I just said is true, then it follows that any piece of philosophy (when viewed from the perspective of not-the-author) has two objects:

the putative area of study, and

the underlying psychologies of people who work in it (I was going to put this in italics, but I think I’m close to my quota for that in this piece).

Of course, you might say that philosophy only cares about understanding in such a way because it’s a necessary step on the path to truth. This is a reasonable take, and part of why I think it’s reasonable to characterize truth as the most critical aim of philosophy.

But (as you might know), philosophy doesn’t have an excellent track record when it comes to actually reaching the truth in some matters. I hear we’ve been arguing about justice since Plato, or something like that. So maybe in an abstract, normative way, truth is the aim of philosophy. But in a down-to-earth, descriptive sense, understanding fits the bill.

What’s the upshot of this?

As Lam indicates, heavily peer-reviewed articles in philosophy are the devil, as they obfuscate the psychologies of people who develop and propound particular philosophical arguments. This makes it a lot harder to understand what the hell’s going on (sociologically speaking) when it comes to a given part of the field, consequently arguably making progress in philosophy harder (arguably). Especially if articles are less interesting and gain less of an audience as a consequence.

(it goes without saying there’s a balancing act to this—some level of pre-publication of editing and feedback is beneficial, and being able to intuit an author’s potential fallibilities is less important than being complete in some contexts and when it comes to some subject matters than in others, but that’s not the piece I’m writing)

I think the ~storied~ continental-analytic feud comes, in large part, from a disagreement about how tolerant you should be about getting some things wrong, if it makes it easier to come to understand something of significance. Continentals want to chart new territory, and it’s okay to them if, like, 96% of what they write would receive low marks from cosmological fact-checkers. It’ll probably help some readers come to a better understanding about something. Better than doing abstruse pseudo-math nobody cares about!

In philosophy, it’s best to be both right and novel. If you can’t be both, be one or the other (assuming you still make good arguments). Being both wrong and old-hat is complete garbage. Hot take, I know.

Anyway, I hope this piece arrived at the truth, or at least came close to it. If not, though, I hope it helped you understand something. 😬

Awesome essay John, thanks so much for engaging!